kth cheapest wine in linear time

Imagine you need to purchase some wine for a party. You’d like to follow the sage advice of this skit:

How can you find out which wine matches the criteria of “second cheapest wine”? Most programmers likely think to themselves, “sort the wines by price, then take array element 1.”

1

2

3

4

5

function cheat(array, k) {

return array.sort(function(a, b) {

return a - b;

})[k - 1];

}

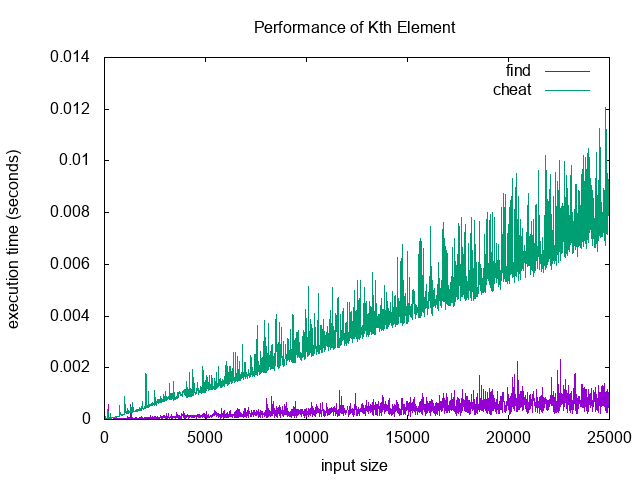

This works, but is O(n log n). We can do better; compare the above cheat to a find I implemented:

find is O(n)1. So what’s the trick? How can we cut the log n factor off? There’s a few strategies.

One “trick” is that to return a kth statistic, we don’t need a fully sorted array. In fact, we’ll stumble over the kth statistic as soon as the kth element is sorted. This observation is the basis of quickselect, which has its lineage, unsurprisingly, in quicksort. For both algorithms, the key is in a subprocedure usually called partition:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

function partition(array, from, to) {

var pivotIndex = getRandomInt(from, to),

pivot = array[pivotIndex];

swap(array, pivotIndex, to);

pivotIndex = from;

for(var i = from; i <= to; i++) {

if(array[i] < pivot) {

swap(array, pivotIndex, i);

pivotIndex++;

}

};

swap(array, pivotIndex, to);

return pivotIndex;

};

In partition we get a partially sorted array based on a pivot. The invariant followed is that the pivot will be in its final sorted order in the array at the return. Sometimes, this may incidentally result in a totally ordered array after partition. For instance:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

// for pivot = 2

// array before partition

{ array: [ 9, 0, 1, 3, 2 ] }

// array after partition

{ array: [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 9 ] }

// for pivot = 1

// array before partition

{ array: [ 2, 0, 9, 3, 1 ] }

// array after partition

{ array: [ 0, 1, 9, 3, 2 ] }

Notice that if the kth we want (adjusting for arrays starting at 0 by subtracting 1) is the same as the final position of the pivot we chose, we’re done! Here’s a closer look at the execution of the partition:

1

2

3

4

{ array: [ 9, 0, 1, 3, 2 ] }

{ array: [ 0, 9, 1, 3, 2 ] }

{ array: [ 0, 1, 9, 3, 2 ] }

{ array: [ 0, 1, 2, 3, 9 ] }

You can see we have to swap the number of elements - 1 to get everything bigger than 2 ahead of it, and everything less than two behind it. We don’t want to have to do that for every single element. Now the question becomes, how can we make the number of times we need to call partition smaller than a full sort? In fact, given we’re doing essentially n operations in partition we must find a way to do that only log times, so that we can end up with only n operations total. If we did partition for every element in the array, we’d be doing n² operations1.

If you’ve ever implemented binary search you already know the solution: you need to consider less of the array on each iteration of quickselect. We can do this in our case because of the guarantee partition provides: our pivot’s final position can be compared against the k statistic we’re looking for, and we can ignore the other side of the pivot. For instance, if in the above iteration our k is 2 (the 2nd smallest number, which is 1), when we see we’ve found position 2 (corresponding to k=3), we can ignore everything beyond our pivot because we know it must necessarily be larger than k, because k < pivot < pivot+n.

In order to do this in place (avoiding tons of needless allocations bloating our memory) we’ll use two references to keep track of what part of the array we’re still searching in. We’ll then parameterize our recursion (if we use recursion) that way.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

function quickselectRecursive(array, from, to, statistic) {

if(array.length === 0 || statistic > array.length - 1) {

return undefined;

};

var pivotIndex = partition(array, from, to);

if(pivotIndex === statistic) {

return array[pivotIndex];

} else if(pivotIndex < statistic) {

return quickselectRecursive(array, pivotIndex, to, statistic);

} else if(pivotIndex > statistic) {

return quickselectRecursive(array, from, pivotIndex, statistic);

}

};

Recursion carries the risk in many languages of exhausting the stack. I’m using a recent enough Javascript that I have TCO. But if I did not, I could translate the recursive function into an interative version. My process for that refactoring is basically this: 1. Switch my base case (pivotIndex === statistic) to a negated while conditional, 2. replace function calls in statements with variable assignments.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

function quickselectIterative(array, k) {

if(array.length === 0 || k > array.length - 1) {

return undefined;

};

var from = 0, to = array.length,

pivotIndex = partition(array, from, to);

while(pivotIndex !== k) {

pivotIndex = partition(array, from, to);

if(pivotIndex < k) {

from = pivotIndex;

} else if(pivotIndex > k) {

to = pivotIndex;

}

};

return array[pivotIndex];

};

Anything comparable could be partitioned this way. The most common use case I think would come up is finding the “top” statistic, for example the user with the highest comment count, or whatever; though in practice, almost anywhere you’d use this you’ll sooner reach to select count(*) first. That said, this is a personal favorite algorithm of mine: when I first encountered it, it seemed like magic to me.

-

Note that the worst case performance of quickselect is O(n²), because it could be the case the pivot doesn’t divide your array roughly in half (so you only clip off one element at a time) and thus fails to cancel out the square. This is why we use

getRandomIntto select random pivots. A deterministic alternative is to take the median of medians instead. ↩ ↩2